Aunt Jemima. For many of us, we haven’t given much thought to the name besides around the breakfast table. Her namesake fluffy pancakes and sweet syrup have graced morning tables of Americans for decades, and a glance at her image or mention of her name brings about fond memories of starting our days with a hearty breakfast.

The Story of Aunt Jemima

But who exactly is Aunt Jemima? Many of us happily consume goods, but we don’t stop to think about names like Uncle Ben or Betty Crocker. Food journalist and historian Toni Tipton-Martin has, and her research on Aunt Jemima happened well before the current rhetoric came about. She debuted her James Beard Foundation award-winning book The Jemima Code, Two Centuries of African American Cookbooks in 2016.

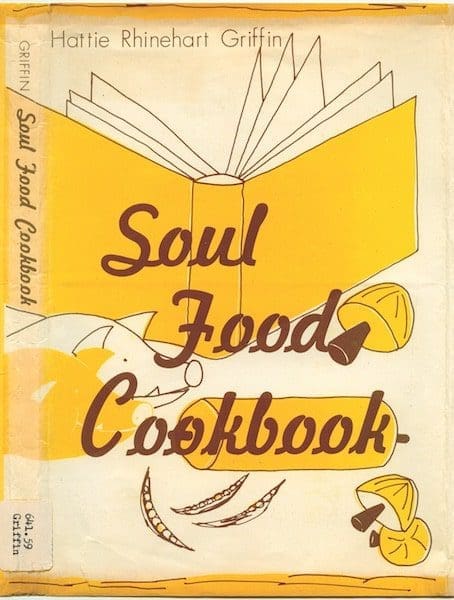

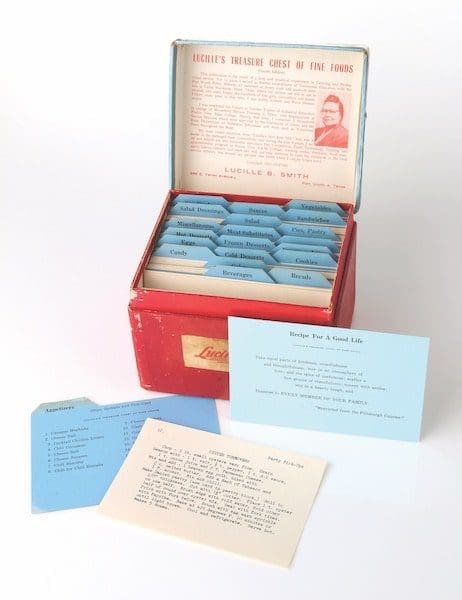

Well Beyond Soul Food

The book is hailed as “a beautiful and essential corrective” by The New Yorker and a “beautiful compendium of two hundred years of nearly invisible work by African American cooks” by New York Times Magazine.

The Jemima Code gives readers the key to unlock what has long been disguised. Tipton-Martin’s most recent book, Jubilee, contains 125 recipes from black chefs, which takes both the palette and mind well beyond the soul food usually associated with African American cuisine.

Black women are well versed in the culinary arts and have been for generations. Many of them were in charge of household kitchens during slavery. This continued through the 1960s when many of them worked for affluent Americans who could afford to have help. These closeted, or ‘kitchened’, women are responsible for both the comfort food and advanced culinary dishes that have long been attributed to those with far fairer skin tones.

What’s in the name?

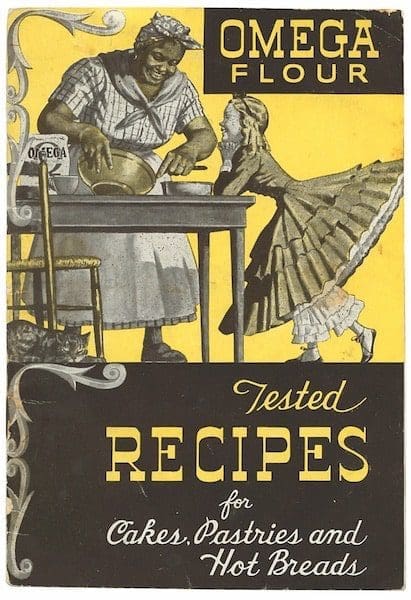

And the name? Just as chefs utilize the ingredients they have on hand to make a “kitchen sink” meal; likewise, Aunt Jemima is a combination of the best parts of many African American cooks.

As a selling point, many Americans grew up eating dishes prepared by black women. So, a friendly conglomeration of personas, styles, and recipes were combined to create a somewhat familiar woman to represent them all. It also gave the purchaser hope that they could cook with the same alchemy for which African American women were known.

As Tipton-Martin stated in The Jemima Code, “Historically, the Jemima code was an arrangement of words and images synchronized to classify the character and life’s work of our nation’s black cooks as insignificant.”

But their skills and contributions were anything but trivial.

The Legacy

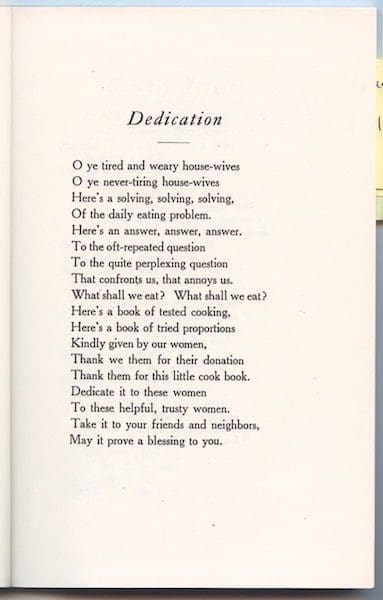

Despite being denied formal education, the black legacy lived on through the spoken word. “They told stories on the front porch, during special occasions, and at celebrations. They transferred cooking techniques while working side by side or sharing a meal together,” Tipton-Martin wrote.

When enjoying a meal, keep in mind the history that encapsulated the knowledge we have today. These African American women discovered and perfected many of the flavor combinations, temperatures, and ideal cooking times.

These were the women who laid the foundation many years ago.